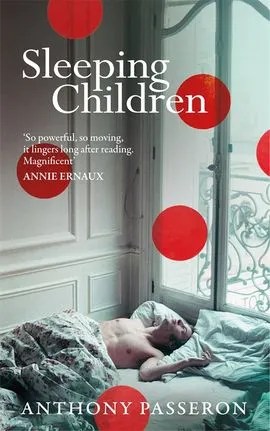

Another gift from my fellow bookclubber, this autobiographical and historical novel tells the story of the early years of the AIDS pandemic. In parallel chapters, we read about the narrator’s uncle, Désiré, the family’s golden boy and eventual heroin user who becomes an early case of AIDS, as well as the entire family saga before, during, and after his death, including the brief life of his daughter, Émilie. In the alternating chapters, we read an abbreviated history of the research and discoveries through the first dozen years, from recognition of the disease, identification of HIV, and development of treatments, as well as the personalities and egos involved and the misinformation and systemic challenges to progress and results.

Another gift from my fellow bookclubber, this autobiographical and historical novel tells the story of the early years of the AIDS pandemic. In parallel chapters, we read about the narrator’s uncle, Désiré, the family’s golden boy and eventual heroin user who becomes an early case of AIDS, as well as the entire family saga before, during, and after his death, including the brief life of his daughter, Émilie. In the alternating chapters, we read an abbreviated history of the research and discoveries through the first dozen years, from recognition of the disease, identification of HIV, and development of treatments, as well as the personalities and egos involved and the misinformation and systemic challenges to progress and results.

Seeing the trajectory of the individual cases alongside the timeline of the research brings home the personal and global tragedies of that time. The family story, told as an investigation by a nephew trying to reassemble the story for posterity, reveals the initial misunderstandings and shame of HIV and AIDS for the infected and those around them. When the only things “known” about it were that it affected only gay men and drug users, a positive diagnosis meant more than a death sentence – it meant you were one of “those.” In a small rural community, “those” were unacceptable, the “sleeping children” collapsed in doorways and alleys. The family’s inability to acknowledge the truth about Désiré’s life and eventual death required levels of denial and dishonesty that rent the family apart.

For the researchers, the initial work of getting heard and the disease recognized was matched in difficulty with the efforts to harmonize research theories and directions. The divisions in the community, led primarily by the egos of those who needed their theories to be the accepted ones, as well as the conciliations of the publishers to those egos, meant new information was withheld or questioned. The result was delays in abandoning incorrect theories or considering new ones, at huge human cost. At the same time, the necessary detachment of the researchers did not reduce their compassion for the communities affected by AIDS. The French researchers are the primary heroes in this story, with the Americans (researchers and publishers) being less heroic, which may be the reality or just the perspective of the French author; however, that the researchers eventually awarded the Nobel prize for this work were both French perhaps supports the author’s view.

I enjoyed this book for the writing and the unique way of presenting this history. The family saga felt sad and true without being melodramatic, and author/narrator’s journey to assemble this past adds an additional layer of realism. Seeing this alongside the research story reinforces the human impact of research work, with the researchers’ steps and missteps, along with the political decisions, emphasized through Désiré and Émilie’s fate.

As a somewhat insider to the research world, I have sympathy for the researchers and their work. The failures of experiments and trials, the impedance of progress by competition and ego, the political and public pressure to rush and also get it right the first time – these are all real facets of research work like this. The decisions about how to design studies, how and when to change or stop trials, and who to include in those trials, all can seem cruel and harsh to those urgently seeking answers and cures. The reality is science requires a methodical and impartial approach, along with a suspension of expectation – the hypotheses must be lacking in any presumption of the “right” answer, otherwise bias affects the outcomes. Researchers and the public may want a certain outcome, but must design the work so the outcome is real rather than desirable.

All of that can be difficult for those affected by the disease to accept or understand. In the midst of personal suffering, such impartiality can seem cruel, designed to cause more suffering. (I remember taking a call from a man in Alberta, angrily demanding his mother be allowed to access a research project only accessible to BC residents. And I heard the accusation, “Where’s your compassion?” on more than one occasion.) When a new illness is rampaging through our world, and we have little information or understanding, the desire for a solution, a cure, a return to “normal” can cause irrational behaviour, leaps of faith and logic, and costly mistakes on both the personal and global scales.

This book does a great job of telling both stories and portraying the tragedies of the early years of AIDS and HIV at many levels. The author’s focus on the/his family story, documenting it “to ensure that something survives”, is effective and powerful.

Fate: I will pass this along to another reader.

4 – published 2025 (the translation)

7 – debut

11 – referral/chosen

13 – somewhere I’ve never been

19 – based on true

21 – translation

25 – new author to me

27 – a gift

Leave a comment