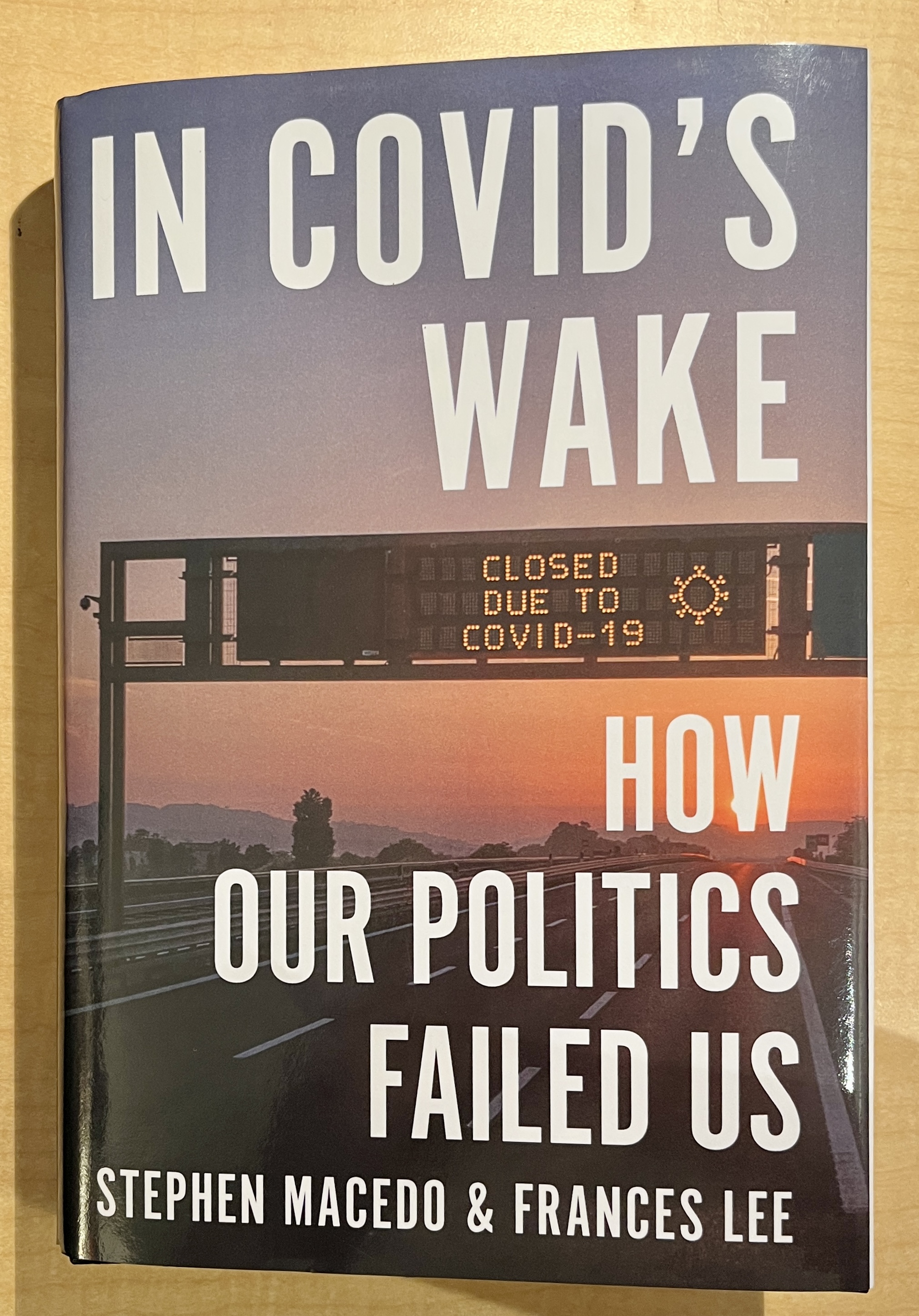

Short version: In Covid’s Wake presents an excellent overview of the policies and actions in several regions of the world (primarily the US) during the Covid-19 pandemic, evaluating these for lessons learned for future crises. The authors do an excellent job analysing the rationales for the various approaches and the outcomes and impact on the pandemic progress and society more broadly. Part history, part politics, and part social science, the book is an important walkthrough of what happened in the recent past, and providing a cautionary tale for the future.

Short version: In Covid’s Wake presents an excellent overview of the policies and actions in several regions of the world (primarily the US) during the Covid-19 pandemic, evaluating these for lessons learned for future crises. The authors do an excellent job analysing the rationales for the various approaches and the outcomes and impact on the pandemic progress and society more broadly. Part history, part politics, and part social science, the book is an important walkthrough of what happened in the recent past, and providing a cautionary tale for the future.

Full review: A good friend and I meet regularly for coffee or lunch. Occasionally, talk turns to “the whole Covid thing”, especially my own experience, but also about the current state of science since “the thing”. I always appreciate our candid, critical, and open discussions, although I feel bad when we uncover something challenging one of their long-held beliefs.

So, I was pleasantly surprised when they recommended episodes of the Princeton UP Ideas Podcast, featuring interviews with each of the authors. After listening to both, I bought the book as essential reading for me.

In Covid’s Wake began with a much broader premise, to look at political polarization across a range of policy issues. However, as became clear early in the writing, the Covid pandemic had several interesting features and failures on the policy and politics front worthy of its own book. As the authors note in the introduction, many of these issues were not being studied or reported on, and the opportunity and necessity of their study became clear. The result is this well researched and transparent assessment of pandemic policies (primarily in the US, but with some international considerations and comparisons) with the aim of providing lessons for any future pandemic. Not quite a textbook, it is more academic than mainstream non-fiction, but the material is highly accessible, engaging, and well-presented and ‑written.

Starting with the early days of the pandemic, the book follows the decision-making, policies, and mainstream media, looking at who-said-what and who-knew-what-when to reveal the failures of public officials on all levels. While not explicitly a search for blame, there is a healthy amount of finger-pointing and identification of failures of accountability. The primary failures were: treating the virus like an enemy to defeat (the war on Covid); presenting things as certainties when there were really considerable variabilities; confusing the different types of risks in various situations; suppressing informed opinion and demonizing experts questioning the narrative; prioritizing control of Covid at the cost of any other population health factors, including well known social determinants of health.

The original premise was to study the relationship between politics and policy: does political polarization influence public policy implementation? The answer is yes, although the data as presented was less compelling on this specific point. While the charts and interpretations show Red/right states were less restrictive than Blue/left states, the resulting Covid outcomes data are not as dramatic as one might expect; there are differences but not stark, and given the many variables (especially timing and clarity of messaging) between jurisdictions, the dots didn’t always connect. Although not explored in great detail, the impact of polarization on vaccination rates and the post vaccine periods are more striking, but still not slam dunks IMHO.

Much more interesting was the detailed presentation of the decision and policy timelines in the US and global communities in the early days of the pandemic, the drama of the “origin story” story, the policies around speech and information, and the politicization of science itself. To discuss all of these would be to completely recapitulate the book, so I’ll focus on the pandemic’s early days.

In first months of 2020, when word of a strange flu was emerging, policy makers turned to two sources for guidance. The first was the various pandemic plans developed, updated, revised, and refreshed over the previous 20+ years. With little exception, these agreed with each other: non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as lockdowns, masks, and physical distancing would do little to prevent the course of a respiratory infection in society; further, the other costs of NPIs, including to social determinants such as mental health, nutrition, education, and equity, were incalculable and likely to be very high.

In other words, the prevailing science prior to Covid recommended minimal and targeted interventions aimed at protecting the most vulnerable (which was not everyone) while allow the rest of the population to continue close to normal. The authors do a great job of tracing this back over the past few decades, and all the way back to the influenza pandemic 100 years ago. The wisdom of these ages acknowledged the reality of a respiratory virus: once it is in the community, and in the absence of an effective vaccine, attempts to control or eliminate the spread are futile and incredibly costly. Focus should be on the vulnerable, and treatments and control interventions should be as low impact as possible.

Those earlier plans also agreed that modelling, while interesting, should be a part of, not a substitute for, policy making. This latter point is most tragic this was to this source most governments turned to and then ultimately relied on, ignoring all the previous plans. To “work” models require ignoring most of those uncertain elements – including economic costs and the impact on other health dimensions – and instead focus on the projected impact of interventions along limited and easily measured dimensions providing clear signals, such as Covid deaths (the distinction between deaths-with-Covid and deaths-from-Covid is similarly ignored as a further confounder of the analyses). With those limitations and narrow focus, the modelling presented the direst outcomes if anything but the most draconian of policies were implemented.

Governments prioritized the models, and so lockdowns, masks, and distancing became the policies of choice, overriding rather than following the science of the previous decades. Most approaches were more primarily driven by politicians desperate to be seen to be doing something, encouraged by publics demanding action over inaction. This is where the polarization trends are most stark if still somewhat weakly correlated – the more left-leaning the politics of a region, the stricter the NPIs, with little (or even inverse) correlation to better Covid outcomes.

Also interesting in the early months of the pandemic were the diplomatic and strategic interactions with China. Without getting into the details of the origin story, the city of Wuhan is universally recognized as ground zero for Covid. In the early months of 2020, governments and agencies, especially the World Health Organization (WHO), used considerable delicacy in their interactions with the Chinese government to maximize the potential of transparency into how Covid was behaving at the frontline of the outbreak. Early assignments of responsibility were quickly derided as preliminary, simplistic, xenophobic, and counter-productive, with many serious people insisting the proximity of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (well known for and richly funded by the US for bat coronavirus research and with a reputation for lax safety protocols) was purely coincidental. Indeed, such assertions were deemed disinformation, often leading to the earliest examples of silencing and cancellation, with social media companies implementing deplatforming policies and policing language and messaging in the virtual public squares. Nowadays, the lab leak theory is considered the most likely, appearing regularly in mainstream media.

These early investigations of the outbreak involved two phases, the first with exchanges of scientific data and information about the virus and its spread in the population, and the second with a visit to Wuhan by a team from WHO. These elements perhaps most influenced the subsequent redirection of global pandemic responses from calmer minimal and targeted approaches to the strict and long-term imposition of NPIs, including travel restrictions deemed unnecessary just a few weeks previous.

While not stated in the book, there is a reasonable theory about China: they had a vested interest in convincing the world to adopt at scale the costly and socially damaging approaches of NPIs, especially lockdown and contact tracing, and so made them appear to be working. Normalizing such approaches in the West, with the consequent divisions in society and crippling costs, could be very appealing to a hostile power playing a very long game. Again, the authors do not assert or suggest this theory, but it is not a stretch based on the trajectory of the response that followed and the state of geopolitics today.

Hindsight is, of course, more revealing than any perspective in the heat of the moments of those early days. However, the authors discuss how the public had – and has – the right to expect politicians and policy makers, along with the expert class they depend on – to apply more reasonable and sober judgement in difficult times and make even difficult decisions on our behalf. One could argue decisions to close schools and impose lockdowns were difficult. As presented here, though, those now seem to have been seen as easier by those in power – easier than educating people about the relative risks and benefits of a less restrictive approach. The catchy slogans of the time – “Two weeks to flatten the curve.”, “Not forever, just for now.”, “Do it for the we and not the me.” – purported to follow the science, but were more akin to the marketing of a preferred narrative and intended to create cohesion and obedience among a terrified populace. Like wartime slogans, the purpose was to sustain fear of an unseen enemy and compliance with difficult social strictures, as well as suspicion and derision of those who did not comply (the fringe minority, the deniers, the anti-‘s).

The public personalities involved only exacerbated the situation. From the polarized political environment, preferring to create havoc for the population rather than let an opponent be correct, to the sudden stardom bestowed upon once obscure but no less ambitious public health officials and scientists, several individuals had reputational interests in advancing approaches that were more “stoke the fear” than “follow the science”. That a feature of such individuals – from politicians to newly famous public health officers – is a healthy ego with a generous amount of hubris, the Covid narratives, once set, were highly resistant to change and very hostile to questions or alternative possibilities.

This leads to the other dimensions covered in the book – suppression of freedoms (speech, movement, and belief), coopting of the mainstream media (with the emergence and attempted suppressions of alternatives and social media), the twisting of the origin story and blacklisting of experts – which I won’t go into further, but highly recommend for anyone interested in learning from history.

As the purpose of the book is to study the failures of the Covid experience as a way of preparing society for a future catastrophe, it does a great job of presenting many cautionary tales. The concluding chapter is sadly quite brief, perhaps because the pandemic is still too close to provide sufficient perspective to translate the cautions into lessons or recommendation. The concluding passage is perhaps the most sobering after all the revelations and reflections of the book:

“The Covid crisis, fortunately, was not mankind’s darkest hour. But the losses of the Covid pandemic will be further compounded if the conclusion political and cultural elites draw from it is that their fellow citizens failed them. That conclusion may serve important ego defense needs, but it will ultimately prove to be a much greater threat to our democracy after Covid than the pandemic ever was.”

This book presents knowledge about and insights from Covid as they currently exist with minimal (but not no) bias. As more is revealed in the coming years, including the long-term impacts of NPIs, vaccines, and social reorganization, it will be interesting to return to this book as a snapshot of the current state of knowledge.

4 – published in 2025

25 – new authors to me

26 – science (NF)

31 – history/politics

Leave a comment