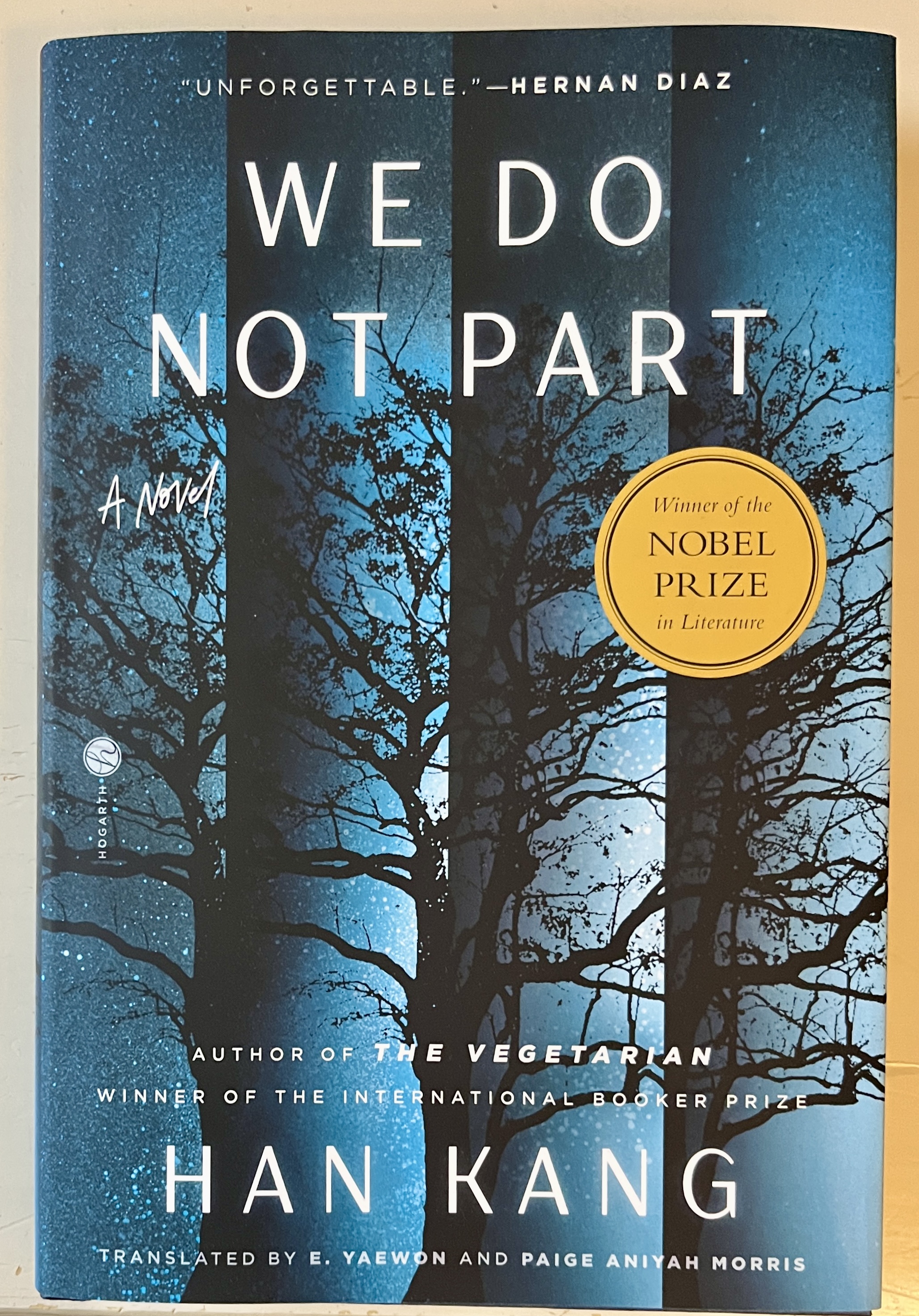

I got this book when I read that the New York Times had selected it for its book club in March. I had also vaguely heard of it at my local bookshop, and with the added imprimatur of the Nobel Prize in 2024, it seemed like a good bet to try out this new-to-me author. Sadly, all that hype did not result in a stunning reading experience.

I got this book when I read that the New York Times had selected it for its book club in March. I had also vaguely heard of it at my local bookshop, and with the added imprimatur of the Nobel Prize in 2024, it seemed like a good bet to try out this new-to-me author. Sadly, all that hype did not result in a stunning reading experience.

Briefly, Kyungha is a depressed and not-very-successful writer, living (just barely) in Seoul. One December morning, she is called to the hospital by her friend, Inseon, who has had an accident and needs Kyungha’s help. The “help” is to travel immediately (during a snowstorm) to Jeju Island, there to save her bird from starvation. Kyungha agrees, and thus embarks on a treacherous journey both natural and supernatural. All of this seemingly for the purpose of telling the story of the 1948 Jeju massacre and the subsequent savagery and misery for islanders. While I learned a lot about this part of history I was unfamiliar with (although I have seen many of these events dramatized in recent South Korean cinema), it was a very convoluted and confusing way to tell this story.

I think a larger point was the generational trauma of such events, as the children of survivors live lives of confused, often unspoken history, subliminal guilt, and unresolvable sorrow and loss. However, this element was both lost in the historical details and then ham-handedly demonstrated by the characters. While Inseon’s inherited trauma was understandable and sympathetic, Kyungha’s was less so, apparently rooted in some extensive reading of history rather than any personal connection with it.

The ghost story bits – with people and birds returning from death to reveal the history – were ineffective, as was the presentation of the history itself. The text switches between standard dialogue (albeit without quotation marks, so not always clear), to italicized text standing in for either: poetic expressions; Kyungha’s interior thoughts; Inseon’s retelling of history; other historical texts real or imagined. All the many layers of this were confounding: which timeline are we in? Who is speaking? This ends up undermining the intensity of some of this powerful history, as the lack of coherency in narration makes it feel unreliable.

All that said, who am I to dispute the venerable Nobels (or even the previous Booker committees)? As little of Kang’s work has been translated into English, it did make me wonder how her very slim body of work could have been evaluated so highly and prestigiously; at the time of the Nobel win, she had just 10 books published, with only five translated into English, so it’s not clear how the committee could evaluate her “intense poetic prose”.

Fate: I’m not going to read this again, so off to the little book library it goes.

8 – female author

13 – set somewhere I’ve never been

21 – translation

25 – new author to me

34 – prize winner

Leave a comment