Short version: Dickens may not be your cup of tea. Ditto for Prince. So the short version is: I really enjoyed this book, learned a lot, and found the comparison to be a fascinating look back at two artists of different mediums and times. If you are interested, but not so much you want to read the whole thing book, the review below is for you 😊.

Short version: Dickens may not be your cup of tea. Ditto for Prince. So the short version is: I really enjoyed this book, learned a lot, and found the comparison to be a fascinating look back at two artists of different mediums and times. If you are interested, but not so much you want to read the whole thing book, the review below is for you 😊.

———–

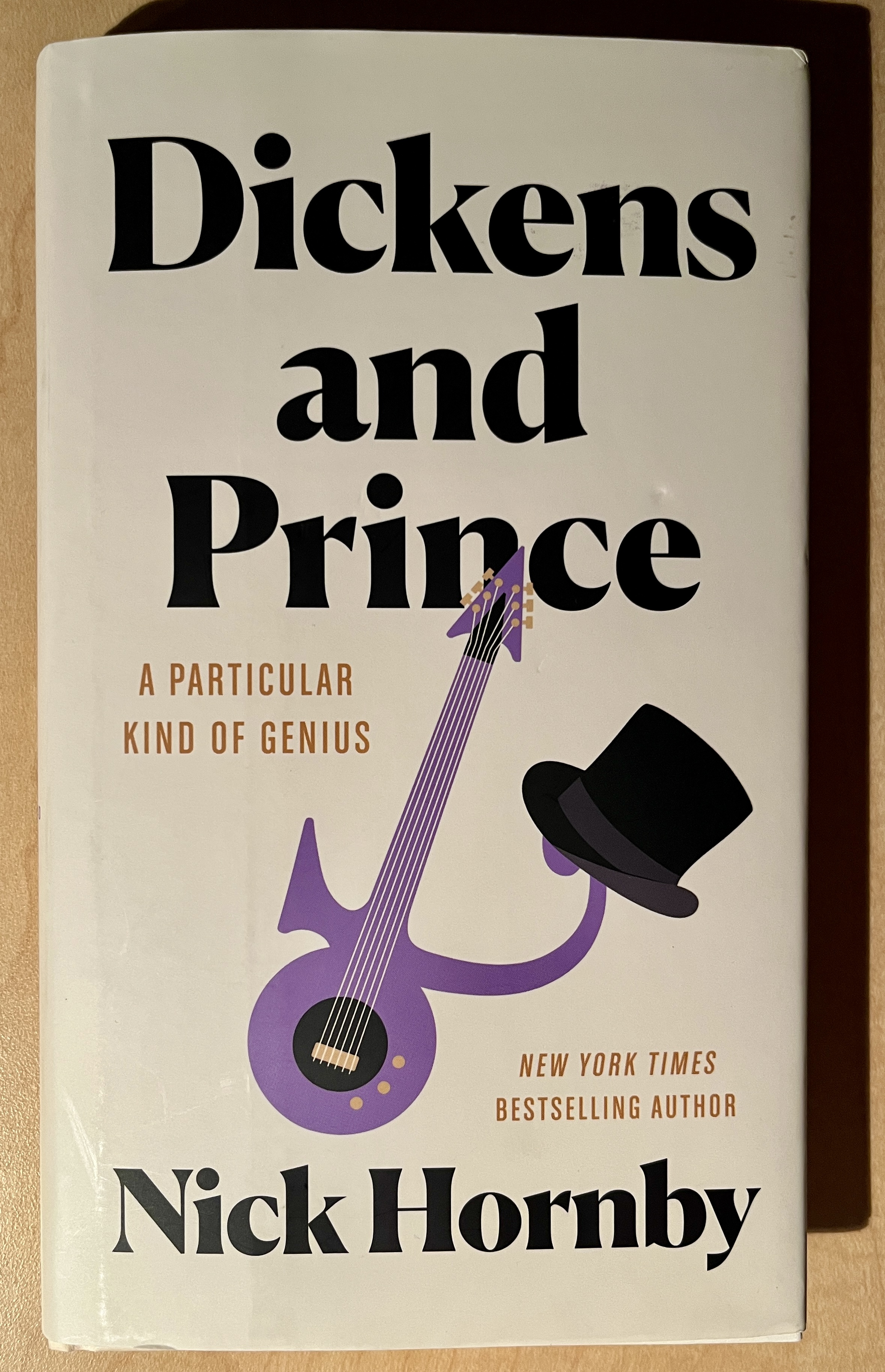

This book was recommended by a friend over a Christmas lunch. While neither Dickens nor Prince are artists I love, they are ones I like enough to learn more about, especially as I was unfamiliar with their actual lives (as artists, they likely prefer it that way). Nick Hornby is an author I’ve not read before, so this seemed like a good way to learn about the three all at once.

Hornby is better known to me for the films of his novels (High Fidelity, About a Boy), each of which explores characters set against their current (i.e., popular) culture. His non-fiction writing is similarly an exploration of popular culture, especially music. He is a big fan of both Dickens and Prince, and this exploration aims to compare-and-contrast their origins, art, and genius and to celebrate their lives and creative output.

At first glance, the similarities between Dickens and Prince are mostly superficial: they were each highly prolific, popular in their lifetimes, sometimes misunderstood, and died at age 58 (actually, 57 for Prince). Hornby compares their life timelines to seek similarities and differences. Both were born in poverty, with absentee parents, and started work at a young age. Both moved into their preferred artistic milieu quite early, immersing themselves in their craft to learn the ropes and begin a path to financial success and independence. They each aimed (and to some extent failed) to hold creative control over their processes and outputs. They had difficult relationships with women, although neither seems to have committed abuse, neglect, or misogyny (Dickens’ 19th century environment notwithstanding). Both died primarily as a result of overwork and the toll of prioritizing their creative demands and their solitariness over their physical health and care from others. And while time will still tell for Prince, it is likely both will leave a lasting creative impact.

It is tempting to interpret their strong desires for creative control as reflecting a perhaps unsavoury perfectionism. However, Hornby puts paid to such thinking by describing their methods for their vast and prolific output. Almost all of Dickens’ novels were originally published as serials in his own or others’ magazines or newspapers. As such, once a chapter was published, there was no going back and editing to revise a storyline or adjust a character – they were already out there. To sustain those stories (and sometimes more than one at a time) over a 1-2 year period, while also writing non-fiction and journalistic pieces, would not be possible for a perfectionist. Once written, the chapters were out of his hands.

Prince was similarly prolific, releasing 30 albums (many of them double) in his 36 year career, making several movies, and performing live around the world at an exhausting pace; after his death, his archive was found to include up to 8,000 recordings of unpublished music, representing centuries of future “new” Prince albums. While he often contributed many elements to his own songs (he was a prodigy in several instruments and considered an expert in music production), his colleagues are adamant about his lack of perfectionist traits: “…he couldn’t wait on perfection…” “Prince taught us perfection is in spontaneity…Create, and don’t ponder what you’ve created.” In this way, he was the prince of good enough – not that you do anything poorly, but that you do just what is needed to make something excellent and then move on.

Another shared approach was live performance. As a way of thwarting plagiarists and asserting his ownership of his writing and characters, Dickens went on the road to read and perform many of his works. Sometimes performing more than 100 times a year, including road trips to America and around Europe, Dickens’ live performances were lauded for their intensity and impact, and reinforced that these were indeed his and no one else’s; the copies were exactly what they were: cheap imitations. Prince was also well known and much loved for his live performances, which were similarly a way for him to demonstrate and maintain his creative brilliance in the eyes of the public and the industry. Unlike many performers (especially in today’s world of auto-tuning, dubbing, and spectacle), Prince’s shows were an eclectic mix of his own stuff, old and new, and interpretations of the work of others. Those who saw him live knew they were witnessing the stuff of legend. Like Dickens’ performances, Prince’s live shows and after shows were not recorded, and so live on only in the memories of those who were there.

In their later careers, both Dickens and Prince suffered from inflated self-importance to the point of self-aggrandizement. While it was true each were cheated or misused in some ways by the promoters and handlers of their respective times, their misguided approaches often backfired, and perhaps contributed to, disruptions to their creative outputs; these forays into the business of their art likely were not good for their health. Dickens chose to lash out at what he perceived as inappropriate fixation on his family and love lives, and he used the 1850’s equivalent of social media to do this: he wrote a letter in the newspaper. Like in modern times, such protestations only served to call more attention to the issue; similarly, like a social media naïf, Dickens kept arguing through more letters, just making the situation worse. As Hornby describes it, Dickens had conflated his status as a famous writer into that of a famous person, thinking the population at large was interested in him; like most famous people, he greatly over-estimated the public’s interest, until he gave them something to be interested in, to his lasting regret.

While not discussed in this book, Prince had a similarly tempestuous relationship with social media, first embracing and then regretting it as a vehicle to distribute and promote his music and videos; his forays into Facebook and Twitter often flopped, as his clever and coy promotional attempts led to confusion and then anger by his fans. His confrontations around his importance were more in the realm of his contracts. He wanted these to reflect his self-perceived greatness – he should be making more than artists who were not as good. Again, genius in art does not translate to genius in business; the deals he made trying to gain glory through money undercut the thing he valued more: creative control. Perhaps this is one humanizing thing of these otherworldly geniuses: they were not good at everything.

Once key difference between Dickens and Prince is likely in collaboration. Despite his dominance in most facets of music creation and presentation, Prince collaborated with many, contributing somewhat selflessly to the careers of others (see Sheila E, Sheena Easton, Sinead O’Connor, and The Bangles, among many others). While he was quite capable of producing songs entirely on his own (indeed, his first albums have no one else credited for songwriting, singing, music, or production), he valued the engagement with others and the opportunity to contribute to the careers of other artists. Beyond his own output, this is an enduring legacy of untold impact. In contrast, except for on the publication and business side of things, Dickens was truly a solo artist. While he did write some adaptations of his novels for the stage, his greatest collaboration could perhaps be with his audience. As a serial writer, his story development was influenced by the public response to the instalments, and as it was the ongoing sales that kept him afloat and enabled his creative potential, he was nothing if not a populist.

Dickens has come to influence literature and culture in ways far beyond his total output. Like Shakespeare before him, his characters and situations live on in language. Dickensian, anyone? How about being a Scrooge? The ghost of something past? Perhaps you would like some more? It remains to be seen if Prince will have a comparable impact within or beyond his medium, but there is no denying his influence in the music world or his legacy. There are a few generations (X and Y, and perhaps even a few boomers) who can’t hear the words “Dearly beloved” without anticipating being called to get through this thing called life. I know I can’t hear the opening lick to “Kiss” without responding, “Uh!”. Perhaps others will emerge over time.

All this to say I really enjoyed this book, both for the history and the exploration of genius. There is no answer to the question, how did they do what they did? They just did, and the genius is revealed in their longevity, breadth of impact, extensive high-quality output, and legacy. The impact of this book is for me to seek out more Dickens, more Prince, and more Hornby. Dickens and Prince would be proud of Hornby: always leave them wanting more.

Fate: I’m likely to revisit this for details and nuggets of guidance on creative work, so onto the overload shelves it goes.

14 – a name in the title

25 – new author to me

31 – history/politics (Our memoir category does not appear to include biography, or I would have used that instead.)

32 – art

Leave a comment