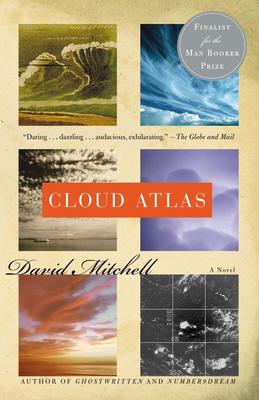

Cloud Atlas, by David Mitchell. Pub 2004

Cloud Atlas, by David Mitchell. Pub 2004

I have been wanting to read this book for years, but have always been daunted by its length and alleged complexity (as per the movie version). After reading The Bone Clocks earlier this year, I was moved to try again.

It’s a difficult novel to summarize. It is a puzzle of sorts, with stories cut into pieces and told in an order that slowly reveals their mysteries and connections. Starting with a lawyer’s perilous journey in the mid 19th century on a sailing ship in the south Pacific, moving through a duet or duel of composers in northern Europe in the inter-war period, on to a feisty journalist investigating a California nuclear power plant in the early 1970s, an elderly book publisher being tricked into confinement at an English seniors’ home in 2012, then the enlightenment of a ‘fabricant’ in 22nd century Korea, culminating in a post-apocalyptic 24th century society in Hawaii. Each story is told in a different style, such as a set of journal entries, a set of letters, and the transcript of an interview. We read the first half of the first five stories, then the entirety of the sixth before getting the conclusions of the others in reverse order. In this way, the connections – some distinct, some tangential – between the stories and characters are revealed. The revelations and resolutions are like a Matryoshka doll taken apart and then reassembled, with the delight of exploring the layers and then bringing the whole together again.

A major theme is the link between deception and corruption, and how attempts to make a world “better” often involve the construction of social systems that require willful avoidance of the truth and the masking of the immoral acts required to keep the system in place. In the earlier periods of the novel, these have to do with class systems and slavery – how society is structured based on these elements which get more immoral and wrong as time goes on but depend on either people willful ignoring them and playing along or society itself actively deceiving people that such things are either not happening or are part of the natural order. As the stories become more modern and into the future, the deception and corruption (still involving versions of class and slavery), and the associated immoral and cruel structures, become even larger and also more possible with the advent of technologies such as mass media, GPS tracking, electronic IDs, cloning and genetic engineering, and globalization.

Perhaps a related idea is about failing to learn from the past, but also how an element of the corruption that enables societies to appear to flourish is the suppression of information, especially about the past, or a refusal to consider or accept the past as a lesson for the present and future. In the post-apocalyptic section, there is reference to ‘The Fall’, the event or period where mankind caused its own destruction, likely through wanton misuse of technology, disregard for the natural environment, and hubris, or some combination thereof. Working backwards from this section, the reader can see how each of the previous eras included some or many of the elements essential for The Fall, making it both inevitable and potentially avoidable at the same time – if only it were recognized, challenged, and averted. This push-back happens in each section, but individuals are somewhat helpless against the tide and tyranny of society (think Winston Smith of Nineteen Eighty-Four).

I enjoyed this book and am glad I returned to and persevered with it. My favourite sections were the 1930s composer (Letters from Zedelghem) and Korean fabricant in the 22nd century (An Orison of Sonmi-451). This is my third David Mitchell novel, and I’ve enjoyed every one of them, despite my initial reluctance about quasi-science fiction and gothic fiction (at least it’s not nature writing).

Fate: I will hang on to this one for reference and comparison with future Mitchell novels.

Leave a comment